I have a dreadful confession to make: I still don’t get visual art. This admission has been a long time coming, I think I first realised this whilst levitating past an advertisement for, you know, Caravaggio or something at the Haywood Gallery on an escalator in the London Underground some time in 2003.

Despite this I’m a regular gallery visitor; I find they provide good grist to the drift; the pacing, the silence and the squeak-squeak of rubber-soled shoes are unmatchable in encouraging thoughts to wonder. Although, perhaps in this sense none have matched the Toledo Museum of Modern Art: marked on maps and street signs, we arrived at an apartment block en el centro de la ciudad to find all the usual signs of an art museum – entrance, corridors, ticket office – but no galleries or exhibitions.

Anyway, frustrated and somewhat shamed by this I’m trying to find a way in. I’m as far as posturing as naif at this point; after all, about the sum total of my understanding currently rests on Hogarth and a long streak of the grotesque. Art Appreciation 101 stipulates it’s okay to laugh at the mischievous dog in the corner of the canvas, permits one to speculate on the knowing look in the sitter’s eye, fine to snigger at the aristo’s get-up to grasp towards a grasp that might be superficial, but at least it’s proper.

With all this in mind I took myself off to the Ludwig Museum, which relocated from its Buda Castle home to a industrial no man’s land turned cultural regeneration centre just north of Csepel some years ago. Though I’m pleased to note that their permanent collection of fairly tautological twentieth-century big hitters now includes selected Hungarian works, I was more interested in Limited Oeuvre, a retrospective of Budapest-born graphic artist Dóra Maurer.

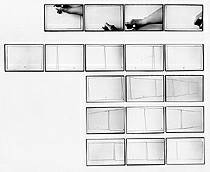

Etude 3

Modest conceptualist Maurer is into the the stuff of things. Her abstract geometries trust form’s own logic. Instead of privileging the action, she’s content to make her early intervention then allow forms to play.

Once we had departed

Maurer’s graphics, photographs and films eschew representation in favour of the pleasures of form. She dirties graphic design and sullies mathematics to make neurotic investigations of proportion and seriality that not only emphasise the physical but also expand the remit of graphics to include traces and residues:

The craft of reproducible graphics, on the other hand, has an aura about it. Its materials have a fragrant smell, the work is a precise one that requires attention. It breaks down into phases, and the concentrated anticipation of what is not yet visible is a good feeling.

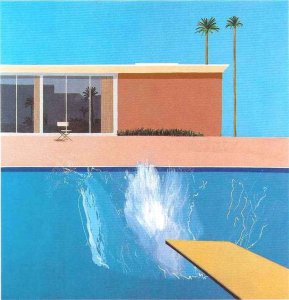

Overlappings, no. 16

Her recent Overlappings force geometry to dance. Maurer’s brightly coloured forms unfurl and overlap like washing in the wind or juggled hankerchiefs. These are forms that aspire towards non-materiality. They reflect, or perhaps parody, changes in the grammar of contemporary graphics, whose forms deny their nature, appear lighter-than-air or quasi-organic. Like the difference between the cover of Esquire magazine in 1972 and the Microsoft Vista operating system, say.